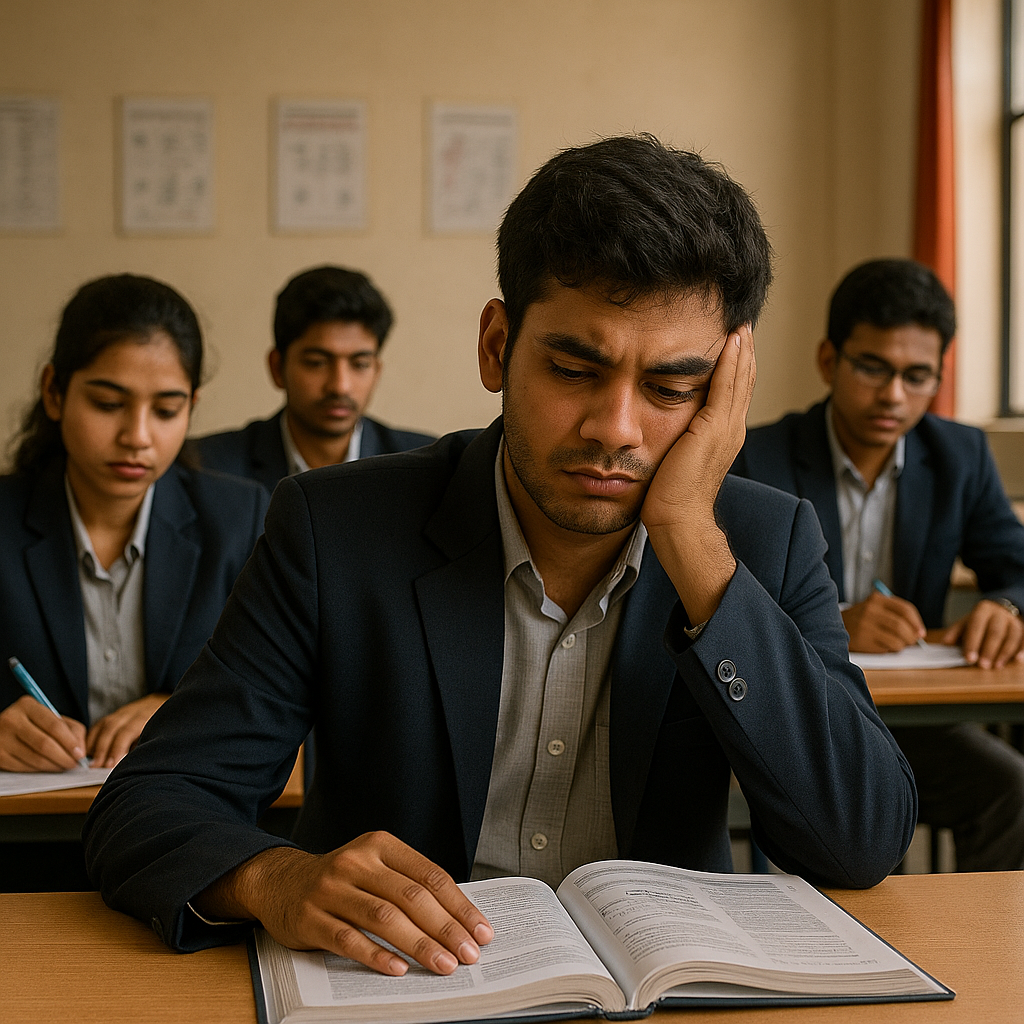

In a modest engineering college in rural Telangana, Ravi Kumar, 22, adjusts the projector in his final-year classroom as he prepares for his campus placement interview. His confidence, however, wavers—not because of lack of ambition, but because, like thousands of his peers across the country, he knows the odds are stacked against him.

Despite earning an undergraduate degree in mechanical engineering, Ravi has never been inside a real factory or worked on a live industry project. His practical experience is limited to lab manuals and mock assessments. “The syllabus is old, and we only get theoretical knowledge,” he says quietly. “But the companies ask about tools and technologies we’ve never used.”

Ravi’s struggle is not unique. It is emblematic of a deeper crisis brewing across India’s vast education system: the widening skill gap between engineering graduates—particularly those from Tier-3 colleges—and the jobs they aspire to secure.

Degrees Without Direction

India produces more than 1.5 million engineering graduates annually, with nearly two-thirds emerging from private or lesser-known regional colleges, often referred to as Tier-3 institutions. These colleges, usually situated in semi-urban or rural areas, vary widely in quality. Many lack adequate faculty, updated curricula, or access to modern equipment.

The consequences are sobering. According to recent employability reports, only 25% to 30% of engineering graduates are considered job-ready for roles in core engineering or technology sectors. A large share end up unemployed, underemployed, or pivot to careers unrelated to their degrees.

“It’s a silent crisis,” says Dr. Vandana Iyer, a professor of education policy. “We’re creating engineers in name but not in capability. The system is churning out certificates, not competence.”

A Broken Link Between Classroom and Industry

One of the core issues lies in the disconnect between academic instruction and industry needs. While the job market demands fluency in coding, data analytics, cloud computing, and practical problem-solving, many colleges continue to focus on rote learning and outdated syllabi.

Further compounding the problem is the lack of qualified faculty. In several Tier-3 colleges, engineering departments are run by part-time lecturers with little or no industry exposure. Internships, industrial visits, or collaborative projects—once considered staples of engineering education—are increasingly absent.

In metropolitan cities, elite institutions like the IITs and NITs attract top recruiters. But for students in regional colleges, placement cells are either underfunded or symbolic. “Sometimes, the only companies that visit our campus are sales firms, not engineering companies,” Ravi explains.

A Growing but Uneven Tech Revolution

India’s tech sector is booming. Startups are scaling, multinational companies are expanding, and sectors like renewable energy, semiconductor design, and artificial intelligence are recruiting aggressively. Yet the pipeline of talent remains fractured.

Some students are attempting to bridge the gap through private EdTech platforms. Courses on platforms like Coursera, Udemy, and NPTEL offer certifications in trending technologies. But affordability, internet access, and English proficiency remain barriers.

The central government has made efforts through initiatives like AICTE’s NEAT program and Skill India, but experts warn that without deeper reform—starting with curriculum modernization and meaningful industry tie-ups—Tier-3 institutions will continue to fall behind.

Reimagining Engineering Education

Reversing the trend will require a fundamental rethink of how engineering is taught and who it’s taught by. Experts advocate for:

- Curriculum upgrades every two years in consultation with industry leaders

- Faculty development programs for technical and pedagogical skills

- Mandatory internships and capstone projects

- Regional innovation hubs that connect colleges with local industries

Some state governments are exploring public-private partnerships to improve technical training and mentoring for rural students. Others are experimenting with hybrid learning models that combine classroom education with virtual labs.

“If India is to maintain its global reputation as a technology powerhouse,” says Dr. Iyer, “it must invest not just in elite institutions, but in the everyday colleges where most of its engineers come from.”