Born in the shadow of communal riots in 1893, Ganesh Chaturthi was transformed by Bal Gangadhar Tilak into a public celebration that bridged divides, challenged colonial authority, and gave Mumbai its most enduring civic festival.

A Riot That Shaped a City

In August 1893, Mumbai witnessed its first large-scale communal riot. What began with the playing of ceremonial music outside a Hanuman temple in Pydhonie spiraled into days of unrest. Textile mill workers joined the clashes, intensifying the conflict. By the time troops restored order, at least 75 people had been killed. The violence left the city shaken, its fragile communal fabric strained.

Tilak’s Cultural Intervention

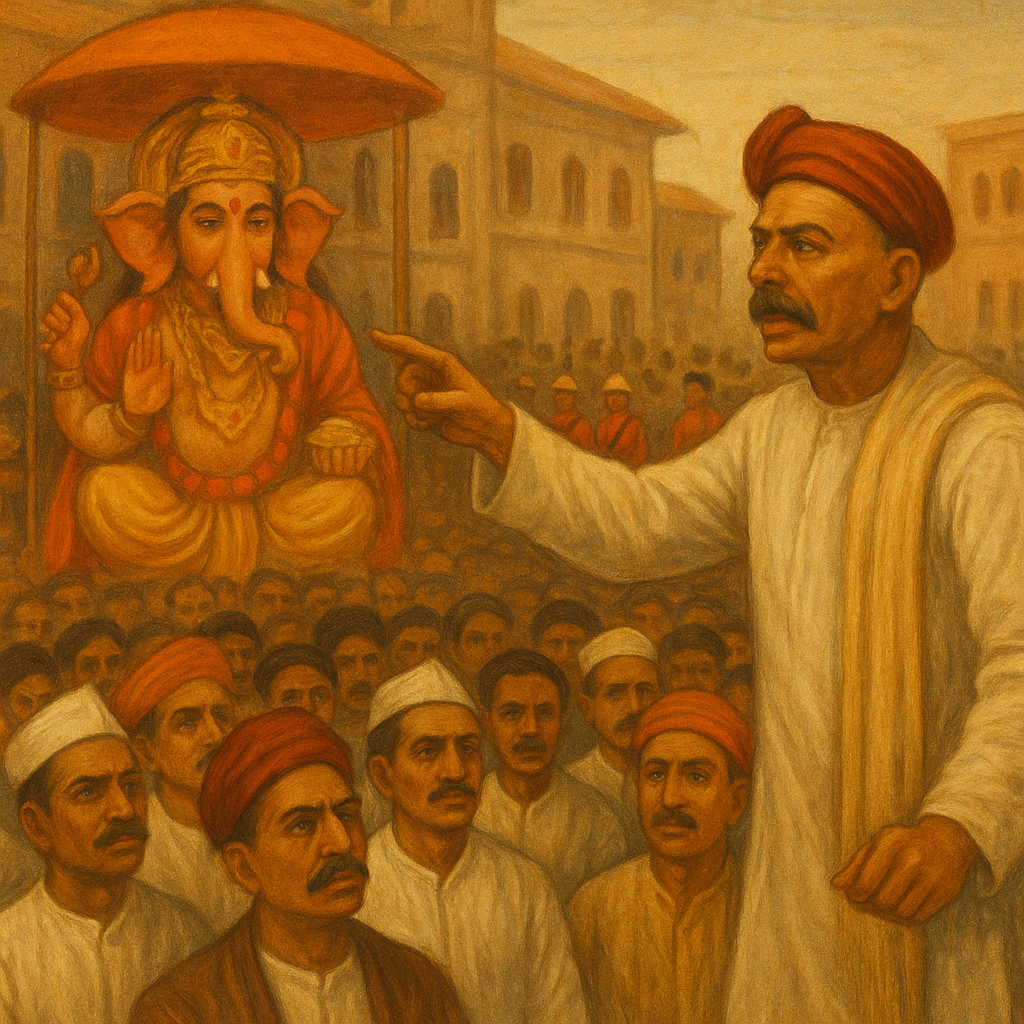

Among those who grasped the moment was Bal Gangadhar Tilak, the fiery nationalist and editor of Kesari. Tilak accused colonial authorities of favoring Hindus during the riots but also saw an opportunity in the chaos. He took Ganesh Chaturthi, until then largely a private household ritual, and reimagined it as a public festival—a shared stage where communities could gather beyond caste or class. Public pandals, collective worship, cultural performances, and poetry readings became instruments of solidarity.

From Ritual to Resistance

Under Tilak’s leadership, Ganesh Utsav grew into more than devotion—it became a platform for political expression. Meetings and gatherings held under the guise of festival activities carried the pulse of anti-colonial resistance. What began as a cultural innovation soon shaped a nationalist identity, drawing in diverse communities—Marathi workers, Gujarati traders, and Marwari businessmen alike.

Over a century later, Ganesh Chaturthi remains Mumbai’s defining festival. But beneath the music, idols, and processions lies its deeper origin story: how a moment of conflict gave rise to a tradition that fused religion, culture, and politics into one of India’s most powerful public symbols.