India, the world’s third-largest generator of electronic waste, is preparing to give discarded gadgets a second life — as power sources for the country’s booming electric vehicle (EV) revolution.

In a landmark proposal, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) has urged the Ministry of Heavy Industries (MHI) to include recycling of old rare earth magnets (REPMs) under the government’s upcoming Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme. The move aims to turn mountains of e-waste — from phones, laptops, and speakers — into valuable materials that can drive the next generation of EVs.

Experts say this initiative could redefine India’s sustainability roadmap, reducing dependence on imports from China, which dominates over 90% of the global REPM supply, and advancing India’s vision of net-zero emissions by 2070.

Marching Toward a Greener, Self-Reliant India

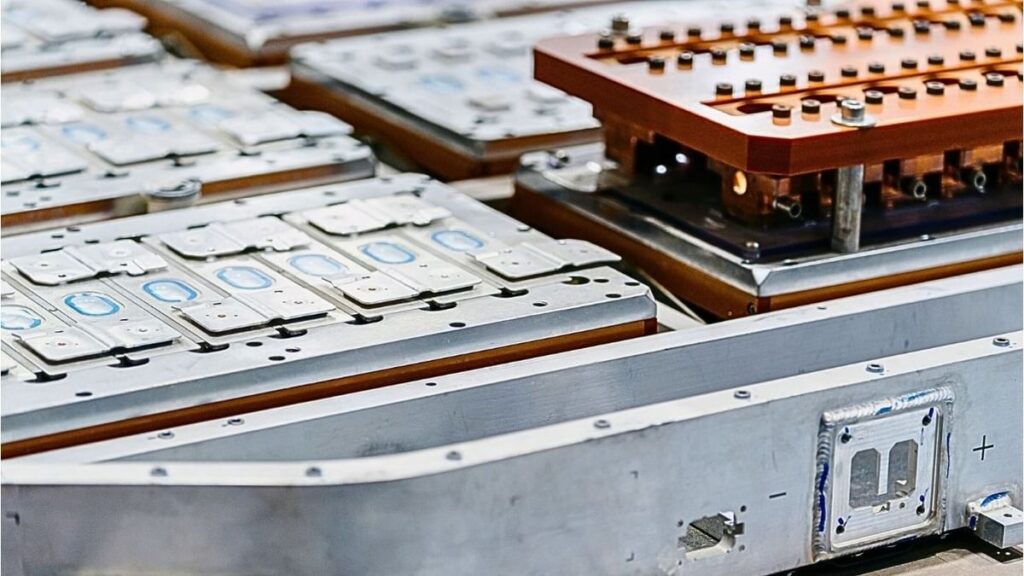

With demand for EVs and consumer electronics soaring, the pile of discarded rare earth magnets — essential for electric motors, batteries, and defense equipment — is growing fast. By promoting organized recycling, India hopes to not only curb environmental hazards but also create a self-sustaining rare earth supply chain.

Officials say that incorporating recycling into the PLI framework would encourage cleaner production, circular economy practices, and long-term industrial resilience — key components of India’s Atmanirbhar Bharat strategy.

China’s Ban Sparks Urgency

The urgency of this push stems from China’s April 2025 export ban on REPMs to India, which disrupted supplies for manufacturers of everything from smartwatches and earphones to electric motors.

While Indian industries have since diversified sourcing, the crisis exposed deep vulnerabilities. Analysts warn that without domestic recycling and production, India’s EV ambitions could hit a roadblock.

PLI Scheme: Building the Backbone of Self-Reliance

Under the proposed PLI plan, five REPM manufacturing plants are expected to come up nationwide, together producing nearly 6,000 tonnes annually.

The government plans to offer capital support and sales-linked incentives to attract private participation and foreign investment.

MeitY, however, insists that recycling must be built into the scheme, arguing that excluding it would miss a critical opportunity to create a closed-loop rare earth economy.

The MHI, meanwhile, cites procedural hurdles, saying recycling currently falls under the Ministry of Mines.

India’s E-Waste Reality Check

According to the Global E-Waste Monitor 2022, India produced 4.17 million tonnes of e-waste in a single year — ranking just behind China and the US. Most of it comes from used electronics such as smartphones, televisions, and laptops, which contain valuable rare earth elements.

Recovering these metals domestically could fuel India’s EV, semiconductor, and defense sectors, cutting reliance on imports and reducing environmental harm.

Industry Sounds the Alarm

The India Cellular and Electronics Association (ICEA) has warned that any delay in stabilizing REPM supply could hit production in critical industries.

In FY 2024–25, India’s electronics output soared to $138 billion, with mobile manufacturing alone contributing $64 billion — evidence that a secure supply chain is now an economic imperative.

Turning Waste into Power

India’s plan to transform e-waste into EV energy isn’t just about recycling — it’s about reimagining industry.

If executed successfully, the country could turn discarded smartphones into the magnetic core of electric motors, powering the clean mobility future of India.

This initiative symbolizes a paradigm shift from waste to wealth — a vision where every obsolete gadget contributes to a sustainable, carbon-neutral, and technologically self-reliant India.

“What We Throw Away Today Could Drive Tomorrow’s World.”

An emerging truth as India turns its e-waste challenge into its clean energy advantage.