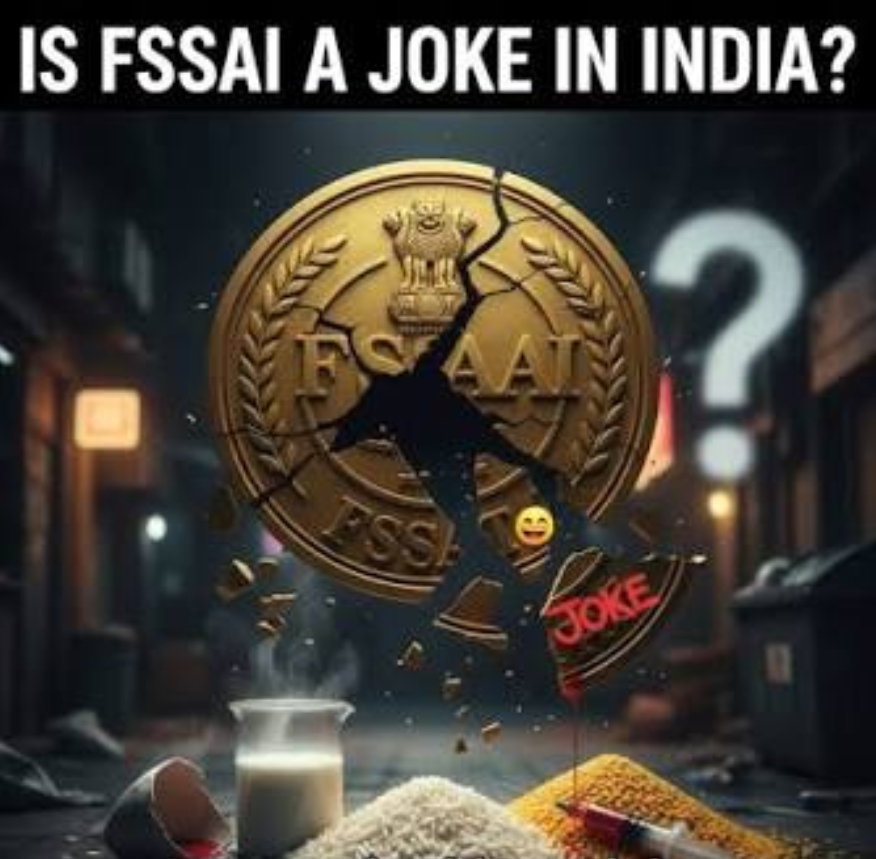

India’s food regulator, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI), has once again announced a nationwide crackdown against food adulteration and safety violations. Raids, sample collections, license suspensions, and penalties are being highlighted as proof of strict enforcement. While the intent appears strong on paper, the renewed drive has also triggered uncomfortable and unavoidable questions from citizens, health experts, and consumer rights activists.

The biggest question being asked is simple but unsettling: what stopped this action for years?

Food adulteration in India is not a recent phenomenon. From synthetic milk and artificial paneer to pesticide-laced vegetables, reused cooking oil, and chemically ripened fruits, reports of unsafe food have surfaced for decades. If enforcement mechanisms existed, why did such practices flourish so openly? Where were routine inspections, random sampling, and swift prosecutions when these violations were becoming the norm rather than the exception?

Allegations of deep-rooted corruption have long haunted the food safety ecosystem. Industry insiders and whistleblowers have repeatedly claimed that inspection reports were manipulated, lab findings suppressed, and licenses renewed despite clear violations. Critics argue that some officials allegedly accepted bribes to certify unsafe food as compliant, turning public health into a transactional exercise. The uncomfortable whispers about “settings” and “arrangements” being made to silence inspections refuse to go away.

The health impact is already visible. Doctors across India report rising cases of cancer, liver failure, kidney disease, and hormonal disorders, many of which are linked to prolonged exposure to adulterated or chemically contaminated food. The damage is irreversible for thousands of families. Yet, accountability remains missing. No senior officials have been publicly named, and very few large manufacturers or brands have faced permanent blacklisting.

Another troubling pattern is selective enforcement. Action often seems to intensify only after videos go viral on social media or media exposes force authorities to respond. This reactive approach raises doubts about whether the current campaign is a genuine reform effort or merely damage control and fine collection.

Consumer groups are now demanding structural reforms: real-time tracking of food supply chains, public dashboards showing inspection data, mandatory third-party audits, and full transparency of lab reports. Without end-to-end traceability and independent oversight, critics warn that the crackdown risks becoming just another public relations exercise.

The core issue remains trust. Unless FSSAI confronts its past failures, fixes systemic corruption, and commits to transparent enforcement, the question will persist—is this campaign about protecting citizens, or protecting a broken system?