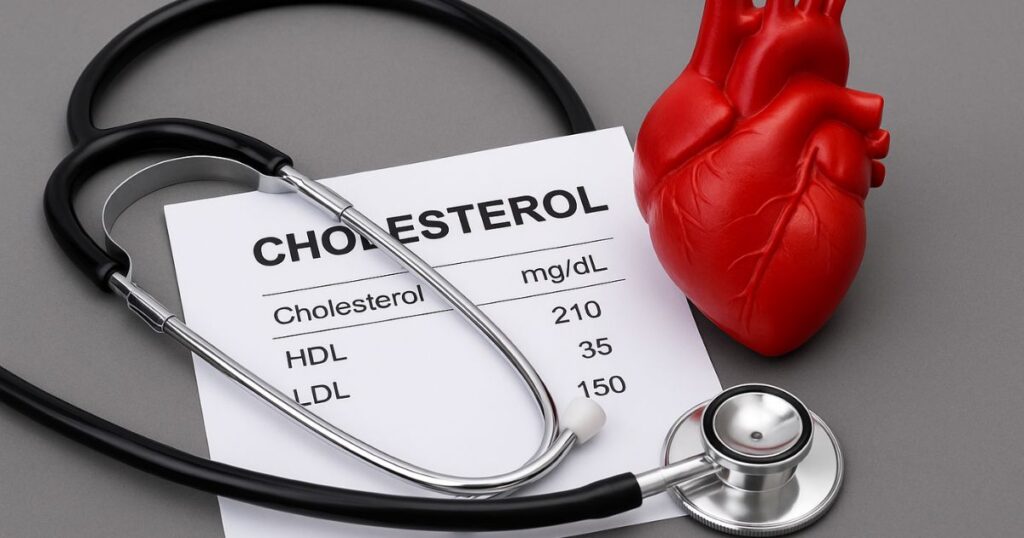

For decades, cholesterol has been cast as the central villain in the story of heart disease. Doctors, pharmaceutical companies, and public health campaigns have warned that lowering it is the key to living longer. But a growing group of longevity physicians argue that this narrative may be oversimplified — and even misleading.

A More Nuanced View

Dr. Jonathan Schoeff, a physician specializing in high-performance and longevity medicine, contends that cholesterol has been unfairly maligned. In an interview highlighted by The Times of India, he described cholesterol not only as safe in many contexts, but essential. It forms the scaffolding of brain cells, helps synthesize hormones, and aids in repairing tissue.

“Cholesterol is not just a number on a lab test,” Schoeff said. “It is part of the body’s adaptive toolkit.”

Beyond LDL: The Subtypes Matter

Much of the public health message around cholesterol focuses on LDL, or “bad cholesterol.” But Schoeff and other specialists argue that the story is more complicated. Small, dense LDL particles — particularly when oxidized — appear to carry the greatest risk, while larger particles may be less harmful.

“It’s about the quality, not just the quantity,” Schoeff said. “Looking only at total LDL misses the nuances of cardiovascular risk.”

Cholesterol as a Response, Not a Cause

According to this perspective, high cholesterol may not always be the trigger of disease but rather the body’s response to stress, inflammation, or injury. In such cases, cholesterol levels rise to facilitate repair.

This reframing echoes a broader movement in longevity science: shifting focus from single markers to systemic health. Cholesterol, Schoeff suggests, should be assessed alongside insulin resistance, inflammation, and metabolic markers, rather than treated as an isolated threat.

The Ongoing Debate

Mainstream cardiology still maintains that high LDL is strongly associated with heart disease and stroke, and large clinical trials support statin therapy in at-risk groups. Critics warn that softening the message could confuse patients and deter them from evidence-based treatment.

But Schoeff’s argument reflects a wider shift: a demand for more personalized, context-driven medicine. For patients, the debate underscores a simple truth — cholesterol is not a singular villain nor a universal friend. It is part of a larger, more complex story of how the body ages and repairs itself.