A recent Supreme Court ruling on the legal classification of the Aravalli hills has sparked a nationwide environmental debate, triggering protests on the ground and a massive online campaign under the hashtag #SaveAravalli. Environmentalists warn that the judgment, if misused, could weaken one of North India’s most critical ecological shields.

The controversy centres around what is being called the “100-metre ruling”, in which the apex court clarified that hills measuring less than 100 metres in height cannot automatically be classified as forest land under existing legal definitions.

While the ruling is technical in nature, its implications are anything but minor.

Why Environmentalists Are Alarmed

Activists from the Save Aravalli Trust, including Vijay Beniwal and Neeraj Shrivastava, argue that the decision could leave vast stretches of the Aravalli range vulnerable. In Haryana, only two peaks—Tosham (Bhiwani) and Madhopur (Mahendragarh)—exceed the 100-metre threshold.

This means large parts of the ancient hill system may lose forest-level protection, potentially opening doors to mining, real estate projects, and unchecked construction.

Environmentalists warn this could trigger a chain reaction:

●Sharp rise in dust and air pollution across Delhi-NCR

●Faster depletion of groundwater and drying borewells

●Intensifying heatwaves and urban heat island effects

●Increased respiratory illnesses and climate-linked health risks

●Long-term migration as regions become less habitable

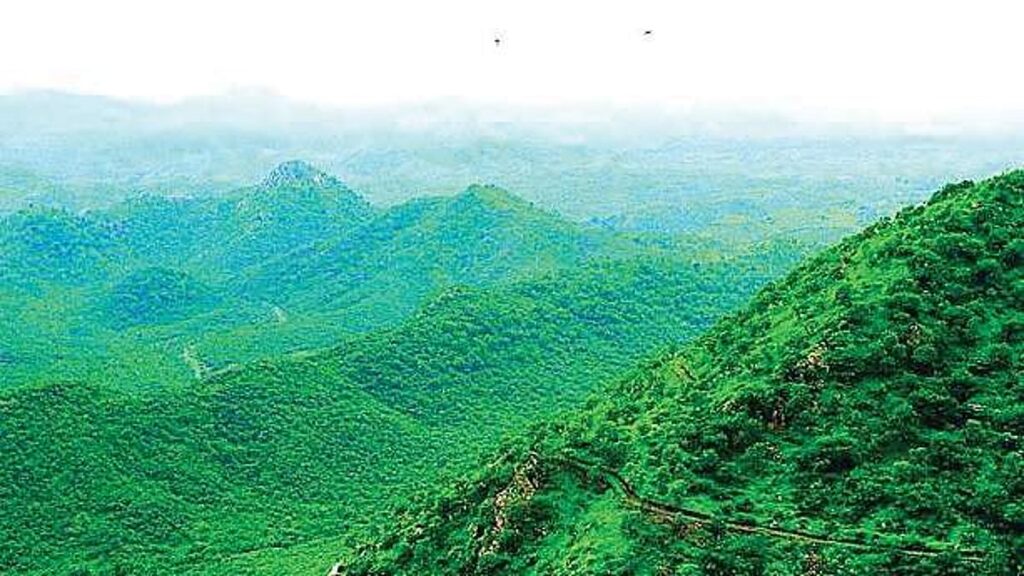

Aravalli: North India’s Natural Defence Wall

Stretching over 800 kilometres, the Aravalli range acts as a natural barrier against desertification, preventing the Thar Desert from advancing toward Delhi and the Indo-Gangetic plains.

Experts note that cities like Dubai experience fewer dust storms due to strong natural and artificial barriers, while Delhi’s worsening dust and smog crisis is closely linked to the degradation of the Aravallis.

Development vs Environment: A Familiar Fault Line

Activists allege that while the ruling does not explicitly permit destruction, it could indirectly benefit mining and real estate interests through relaxed interpretations. The fear is not the verdict itself, but how state authorities may implement it.

Urban planners also point out that Delhi was chosen as India’s capital during British rule partly because it was geographically protected by the Aravallis on one side and the Yamuna on the other, creating a natural climate buffer.

#SaveAravalli Movement Gathers Momentum

The Save Aravalli campaign has announced plans to submit memorandums to district magistrates in over 150 districts. An online petition linked to the movement has already crossed 41,000 signatures, reflecting growing public concern.

Campaigners insist the goal is not confrontation but accountability—ensuring the ruling is not misused to dilute environmental safeguards.

Air, Water and Climate at Stake

Scientific studies cited by activists show that degraded Aravalli zones significantly contribute to PM10 and PM2.5 pollution, especially during winter months.

The hills also play a vital role in rainwater retention and groundwater recharge across Haryana and Rajasthan—regions already battling severe water stress. Further ecological damage could push aquifers to irreversible collapse.

Not the Judgment, But Its Interpretation

Even some legal experts backing the verdict agree that the real danger lies in misinterpretation, manipulation of land records, and diluted environmental impact assessments.

Ultimately, the future of the Aravallis now depends on state governments, regulators, and public vigilance.

Why This Matters

The Aravalli debate is no longer about legal definitions—it is about air quality, water security, climate resilience, and the livability of North India. As activists warn, once this ancient ecosystem is compromised, the damage may be irreversible.